Ajamu X: Full Interview

Interview recorded by E-J Scott on 8.5.2020

Duration 49:41

TRANSCRIPT

Ajamu XInterview by E-J Scott

8th May 2020

INTERVIEWER: Okay, we’ll start the recording now. I’m E-J Scott. I use the pronouns he/they or you can just say your name, and I’m the project co-ordinator for the West Yorkshire Queer Stories project, and today is Friday the 8th of May 2020 and we’re recording during the coronavirus lockdown in the UL, which means we’re speaking virtually, via our computers and so for the record, there’s a third party here, Sonia Sandhu taking on the role of producer. This mean, this explains in part a little bit of the echoey quality that tends to come across as we’re recording and the recording locations. And I am welcoming today for this interview Ajamu – Ajamu can we start with the formalities, could you please tell me your name, your pronoun, your date of birth, where you live and how you identify? D’you want me to do that one bit at a time? [laughter]

AJAMU: Okay, you’re not gonna work me today.

INTERVIEWER: After that we can just chat.

AJAMU: For the record, I’m Ajamu. I was born in 1963, October in Huddersfield, and my birth name is actually Carleton Cockburn, however I changed my name during the late 80s, and I’m currently living in London and I’ve been for the last 30 years. And my pronouns is he/them, [unclear] queer.

INTERVIEWER: Okay, perfect, thank you. And before we get onto the serious stuff, I need to get the inquisitive stuff off my chest, Ajamu. What does a queer black punk photographer like yourself do in lockdown? Do you take dirty pictures all the time?

AJAMU: No, I am busy with my PhD work [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: That’s, tell us about your PhD.

AJAMU: So, basically I’m – my PhD is currently called Dark Room Matter and I’m basically, I’m rethinking the photographic darkroom and the sex darkroom as archives, yeah, in how these places kind of hold memories. And the work I will be working with is objects that people have made or constructed to have pleasure with. And I’m also working with wet plates, which is kind of a 19th century printing process, and so basically a lot of my work is how do we rethink the archive and, basically I’m, I kind of come from the place that actually a lot of the work around black and queer archives, including some of my early work around the archive, is kind of locked into kind of representation and identity politics. And I’m saying, well actually we have to account for things around sensuousness, tactility, touch. It’s because, my claim is that the black queer body is always already an archive anyway and we embody memories, emotions; our nipples and dicks and arses are also archives. And so basically it’s kind of how, how do we rethink the archive outside of space and location and to something that’s more sensitive, more fleshy? It’s because basically a lot of the amazing work around archives historically don’t talk about the materials in the archive. It’s about power structure, decolonisation of these all things around the archive, and so my thing y’know is what is the archive doing?

INTERVIEWER: Is that partly because, a result of your practice as a photographer? Or as your practice as a black queer person? How – and living, living as a practice? Where do these ideas, where does the importance you place on embodiment come from?

AJAMU: Well, basically I – the actual… It comes from, I think – no, no, no. There is a resistance in the wider culture talking about pleasure and the erotic, yeah? And the more that you then drill down, I, I’m, I think that actually, if you talk about let’s say… Photography, right, yeah, right? It’s because lots of black and brown work is looked through the lens of, it’s content, it’s something cultural. What it excludes is process and making. And to me the act of pleasure has to then be part of the conversation around making work or creating something, yeah right? And then my notion of the erotic comes out of kind of my… Audre Lord’s work… whereby she talks about, and the erotic is not a question of what we do, it’s how acutely we are aware in the doing, so when actually, I think then actually if and when one is attuned to the moment or to what’s happening, it means that actually the [unclear] with the body and the skin and the flesh. And then in part, I think then too often our black and brown and queer politics gets locked into what is done to black and brown queer bodies. And it should. And I’m also saying we should also be talking about what we want to be done with and through our own black bodies as well. And then that then is about agency.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, and empowerment, right? This is really interesting – let’s step back to think about West Yorkshire and go back to this idea of the cultural lens. Where did you grow up?

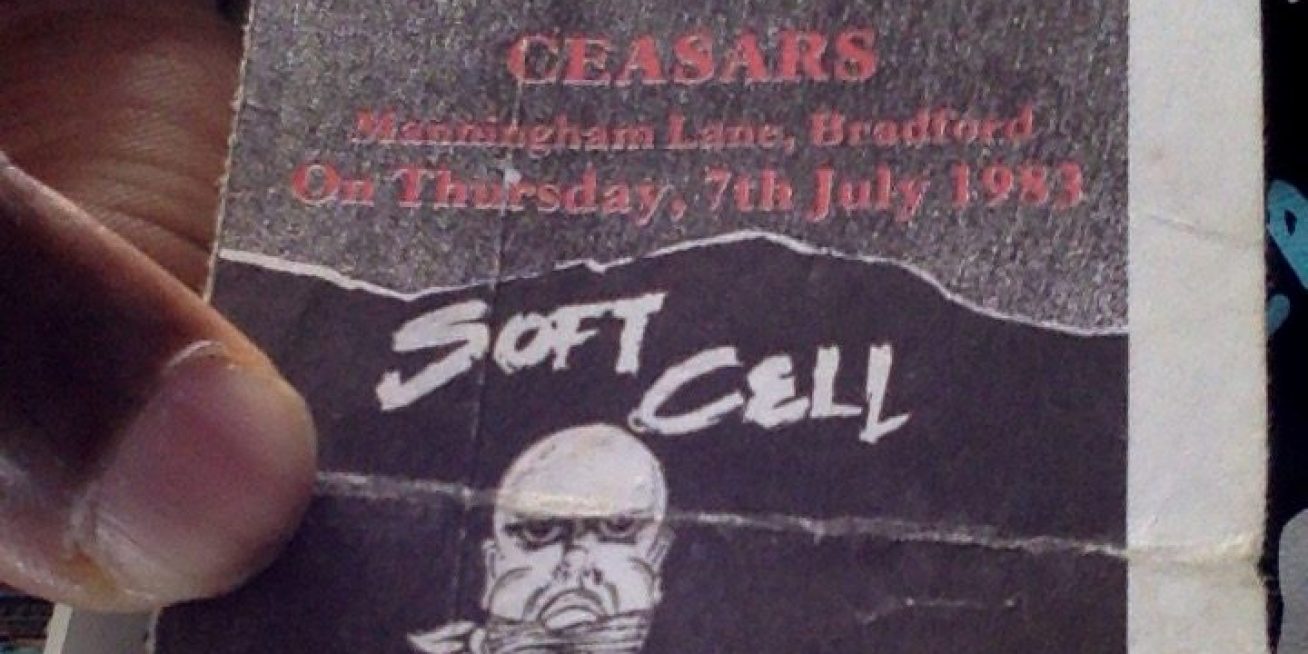

AJAMU: I grew up in Huddersfield. I, I went to, my first school was, [unclear] infants school, and then I went to [unclear] junior, then [unclear] high school, and then [unclear] high school and so basically, it was kind of very mixed neighbourhoods. And basically, my parents arrived in ’61 from Jamaica, and then my grandparents actually came to Bradford in about ‘57/’58, yeah, and so – I have three brothers and two sisters who were born and raised in Jamaica and they kind, they, they’re what you call the sent for kids and they were brought over in the 70s. And so we kind of, it had been kind of very… fixed ideas around masculinity and religion and that kind of stuff. And then basically me, around 16 I kind of like being post-punk or rock or goth or whatever, y’know I was that odd black child walking around child, into this weird music, and y’know and I was into wearing soccer boots and mascara and frilly shirts. And, and I’d, and the person I blame for all this, interestingly enough, is Marc Almond from Soft Cell, seeing Soft Cell on Top of the Pops that year, and it triggered that there is, there is something else somewhere else and then of course he was singing about and y’know Soho and London and whatever, it just opened up this window for me, yeah. And the album Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret was the backdrop to, that was just on repeat, repeat and repeat as a weird kind of – and yeah, yeah, and so basically, I kind of left school.

I did catering. I… I did landscape gardening, I was in the Territorial Army. Y’know, I, there’s an image I have that was taken on the day that Charles and Di got married and so I was stationed in Strensall, just outside York. So, really I’m kind’ve I’m – and then, and then joining the TA, (a) because it was something I could do; and also what you had in this kind of early 80s was the rise of the National Front. Right, yeah, right? And basically a handful of us black guys joined the TA to learn how to protect ourselves. It’s because this is where the National Front was getting trained up, in the TA that was in Huddersfield. So when, so when on one level I had my army greens, my boots, whatever, and then the next minute I got mascara and nail varnish on. And be just working this thing through, and so, so that’s when I became part of as a backdrop, and then I… And then those of us who were kind of marked as being different kind of them kind of, the kind of scene that we entered I was kinda like a goth, post-punk, New Romantic scene, and that’s where you’d see kind of, all kinds of people, not just queer, all kinds of folks just seen as different, cos actually I… Freaks always find each other somehow.

INTERVIEWER: Was that still in Huddersfield?

AJAMU: Yeah, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: What clubs did you go to?

AJAMU: So basically, the, the… the goth club was called Charlies, and that was nearby the actual marketplace… I, where I, where McDonald’s is, there was a club called… Highlights, some- something club and that was upstairs, and then there was Johnny’s Club as well, which was kind of… down, down the bottom of town. And then, of course, Gemini club. And so the first time I went to the club was March the 3rd 1983 on a Thursday night.

INTERVIEWER: How do you remember?

AJAMU: Because, this is what archivers do [laughs] [unclear] and so basically the – the thing about the club was I, around the corner from the Gemini club was the [unclear] Street Club, which was a black club, yeah? And so basically I would stand for about three months across the road from the club just to see who was going past, and then this one night I just literally ran across the street. As the door opened, I just ran straight in, and like, I’m here. So and really, so then that first night I met my first lover, Desmond [unclear]. And so basically while I was in lust at first sight, it was also, it was because we were isolated. It’s because at that time, at this point, I… he was, he was the second gay person that I knew, and there was talk around town that there was this other guy called David Wood, bisexual, and so basically Huddersfield is a small town and basically, and these whispers, and so literally I then went searching for David. And so basically, I’d try and find out where he went, which clubs he’d go to, and so it was really this intense, and then because then I had girlfriends as well. So then I was kinda working out am I straight, bisexual, queer, gay or whatever. And so I, this was happening in this very, very small town, and it is a really small town. And the way that I would then leave the town was then to go clubbing in Leeds, New Penny. I’m, I’d, New Penny and there was Rock Shots, and there was God’s Waiting Room, which was another club, I would go, all the gays would go. And then Manchester at the scene, and so really. And then, and then also I went travelling to London and the queens would call me ‘the National Express queen’.

INTERVIEWER: Because you’d travel?

AJAMU: I’d travel. I’d have like a £9 return or something daft. I’m, so at this point there were, there was a newspaper called the Caribbean Times that had in, adverts in, and adverts would say, ‘broadminded guy seeks friend’, and then that was code for, they might be open to something gay or bisexual, or they probably were gay or bisexual or queer. Okay, so then I, that’s how I then, then met guys I through try and… as the newspaper, and then I met guys in Manchester and Leeds, so it’s kind of that’s a kind of a network –

INTERVIEWER: So then was it, you mention the cost, was it affordable for you to between these cities and access this culture?

AJAMU: I, so basically in ’81… was this ’81 or ’80? I was on your YTS, your young person’s, young person’s something – your youth, youth, youth programme, yeah. And also you’d get £35 a week yeah, so that was quite a lot of money in ’81, ’82 I’m talking about, and so really kind of [unclear] travel across Bradford to Leeds and jump on a bus, yeah, yeah, it was dirt cheap. And then, and then David, who was my next boyfriend, I, he drove anyway from Manchester. So, I then, as Desmond then had a car and we could then drive to Manchester –

INTERVIEWER: I can imagine you in that car with the music up.

AJAMU: Oh my God, I was a mess [laugh] I was a mess.

INTERVIEWER: These are the things I wanna hear about.

AJAMU: Oh my God, I was a mess, I was a mess. Yeah, so really I, I, it was just kind of one of those towns where everybody knew everybody, and that’s the nature of small towns. And so basically, a few of us kind of we then left as soon as we can, it’s because it’s one of those towns, either you stay silent or you get out.

INTERVIEWER: Do you go back now?

AJAMU: Yes, I need to go home every couple of months, I try and see my family. I – they’re still there.

INTERVIEWER: What emotions does it raise?

AJAMU: I – Huddersfield, I, I… my family never had an issue with how I looked or dressed, yeah, y’know. So, basically it was outside the family and that there might be name-calling or whatever, I [unclear] people… and even now… the town reminds me of how isolated I was, not just in terms of my sexuality but culturally isolated, politically isolated.

INTERVIEWER: How do you feel about that?

AJAMU: Well basically there, there were, there were just very few spaces to go to that was kind of enriching, apart from the goth kinda punk scene, yeah. And then because I was reading lots of like art magazines, I was kinda like in that headspace, and then turning points was in 1995 I, I went to Leeds and saw the Last Poets and a group called Turbo. And then, basically, that’s when I think kind of race really kind of, when race reared its head, it’s like around a black politic. And then basically I kind of became this angry black man around town because I was then reading Malcolm X and all this kinda stuff, and in 1995 – I will show you a copy at some point – I created a magazine called Black Magazine and I – Black Magazine, we printed 500 copies and there was a pull-out yeah, and there was articles around sickle cell and there was an article called ‘Wake Up Niggers’, there was an article called, ‘We Hate You White South African Bastards’. And so, that was like, [Paul ?] from Leeds, and Victor, and we just kind of created this magazine, just to grapple with all these kind of ideas. And really, that was kinda my experience as a, as a basically, it wasn’t until ’87 coming to the Black Gayness Conference, that then I wasn’t able to bring race and sexuality and mesh them, actually they were still very much kind of separate. And the worlds were separate.

INTERVIEWER: And so it sounds to me like, in actual fact, these experiences in Huddersfield do have a lingering, they do inform who you are now and your work and your –

AJAMU: I think for me I, I’m, I think that I’ve… because I spent so much time in my head in Huddersfield, actually, I think that a lot of my thinking now comes out of that, that space whereby I had to then just think about things. And then also then I’m, I’ve got into photography around ’85, ’86, and so basically –

INTERVIEWER: Still in Huddersfield then?

AJAMU: Yes, I was still in Huddersfield. I would then take images of y’know friends, of carnival, that kind of stuff, but then I would also then take images of the guys that I was attracted to, and those guys were not necessarily aware of my sexuality then, so I was really trying to kind of work, I just worked these things through.

INTERVIEWER: Studio shots or, or outside, or [unclear] shots or passersby?

AJAMU: They were shot in my bedroom that I lived in with, at my sister’s house. I just threw up a backdrop, two household lamps and then – I still have some really out of focus contact sheets of those, of the guys that I was taking, and so really kind of like, and then actually… Ironic – well it’s not ironic, right, yeah – I, the first piece I wrote for Black Magazine was on bodybuilders. And then four years later, that’s then, that then in London, cos I’d moved by then, that’s then where the image of the [unclear] comes from, just doing this article four years previously around bodybuilders. So, there’s actually, I’ve always kinda of tried to draw upon being in that town –

INTERVIEWER: It’s almost –

AJAMU: Actually, I think that actually, it did allow me to think about things. Because there was no one around to talk to about those things about. So, hence just thinking experimentally and working it through, so yeah, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: What kind of camera were you using at that time?

AJAMU: My mum bought me a Pentax K1000 from Empire Stores catalogue [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: Amazing. Do you still have it?

AJAMU: No. No, no, I lost it somewhere. It was like £2.50 a week or something, it was like just like yeah Empire Stores catalogue. I’m dating myself. So, yeah, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: It seems to me when you reflect and you go and I hear you talk about, ‘then this happened and I realised that this informed later on’, y’know in your work, it’s almost like there’s layers or process just like an archive. Y’know, just as they work, they way you’re putting together your experiences with your practice and aligning those two things on top of each other, that’s very interesting.

AJAMU: Yes, that’s why I come back to the idea that the black queer body is an archive already, already. And basically our experiences kind of document, if you will, and I guess kind of like that’s how I’m working constantly to, to complicate this notion of archive and memory, and time and place and space. Basically, also, for me, Huddersfield is also in London [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: That was where I was gonna go next. How does it work now in London? It was obviously important to get away to find cultural enrichment in London. It was, it was not as much as an escape, it doesn’t sound to me, as much a craving for information and access, almost. So, you’re now in London – how long have you lived in London?

AJAMU: I moved on the 18th of January 1988 [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: Again with the dates [laughs] And in London what do you do now? Tell me a bit about Huddersfield boy has gone to London and become a working photographer and artist and activist.

AJAMU: Well, for me London was about kind of… For me I turning point really was the first and only National Black Gayness Conference, October the 31st, and also though – so basically, I was living in Leeds now, cos I moved to Leeds around ’84, right. And then I was in Leeds ’87, started photography at Leeds Kitson College and then that September… I was living with my girlfriend still, in Chapeltown, and that September there was talk by David A. Bailey, and the event was run by Mod Salter, yeah, on black photography, yeah. That was September, right yeah? And at this point I was having these tensions with my lecturer, yeah. It’s because I’m, his [unclear] was around technique and then I had this vague idea that photography had to do something, right, yeah. It’s very, yeah it’s very vague. And then the October I came across the portfolio of [unclear] in Gay Times, yeah, right. And then also then, I was then coming across the work of [unclear], Mapplethorpe, [unclear]. And the conference then was in the October, October the 31st. And then [unclear] Richard gave me a copy of [In The Life: The Black Gay Mythology]. Basically, I wrote to the black lesbian and lesbian [unclear] project saying, y’know, ‘I’m a black bisexual man, can I come to the conference?’ and [unclear] responded, yeah.

And so by then, the January I had then moved to London. Basically, I had now come in to family, feeling less isolated with [unclear]. I moved to Peckham first, for about three months, then moved to Brixton, yeah. And of course I then moved into Brixton Housing Collective, and so I grew up in the Collective [unclear] And so basically, and then… and then [unclear] black and queer artists. And okay [unclear] living in a housing co-op, alright I’m living in a housing co-op. And so basically, when I, then my work, started to come out of those kinds of conversations I was having, and so like London was then where I was then able – I started then to call myself an artist. I was like, okay, I’ve been doing photography for X amount of years, maybe I should stick to it now. And then 1990 I then joined – no, ’89 I then joined the Brixton Artist Collective, and then this journey started. And of course, then I created groups, like the Breakfast Club, which was a monthly black gay and bisexual men’s group. The Sex Club I used to run, and the Black Perverts Network. And then also then the magazine cofounded [unclear] founded I was one of those people. And then I was then literally just taking images of black folks at pride and then just working from ideas as well, yeah. And then by 1999, London then became like Huddersfield, in that it became too small, yeah? And I went to then live in Holland for two years, yeah. And then I went to the [unclear] in Maastricht. And then, while I was then in Maastricht, Ruckus came out of that.

INTERVIEWER: Tell us about Ruckus.

AJAMU: Basically I – so Ruckus kind of, so Topher. I met Topher at gay pride in 1989, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: [Inaudible] yeah?

AJAMU: Yeah, so we’d been y’know, best friends and so we’d just been talking for years and years and years and years and years. And then we kind of – Ruckus really came out of frustration about how we felt lots of black queer politics was going. So, basically, I would argue lots of our conversation starts from a deficit paradigm, yeah. And so basically it’s locked into homophobia in black families and communities, racism on the wider gay scene, and then we would say yes and we’d also been creating culture for 20 or 30-odd years, so then actually we can then bring in another layer, so actually we have been creating, so actually Ruckus came out of that kind of frustration about just wanting to have another conversation around being black and queer. And now we’re kind of at where we were reaching our late 30s, so then another dialogue around age also. And then the archive kind of came as a default, and so the archive – we were in conversation with [unclear] who ran the black queer archive at the [unclear], right yeah, and so he’s been a friend of mine since 2001. And so in 2004 we had this idea for an exhibition called Family Treasures, which would look at kind of black queer history yeah. And so we mailed out to everybody, right, yeah, and then nobody responded. Yeah, right? And then we contacted some funders, no names mentioned and they said, ‘well actually, we fund the black cultural sector and we fund the wider white gay cultural sector – you have to fit into one of them’ [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, okay.

AJAMU: And we’re going, ‘no, cos actually we’re part of them and separate from, yeah’. And… and so I got some feedback from some friends, and so what kept cropping up was what history of black queer Britain – what does it look like? Who is it? And then the, in 2005 there came the Queen’s Jewels, yeah? And then of course the word ‘Queen’ was being used as a derogatory term against men who are feminine, yeah. Jewels also refers to the private parts, yeah. So basically, the reason why we chose the title we do is cos actually, if you were born and raised in this country and then you then have then grown up on [unclear] John Inman, Frankie Howard, Kenneth Williams… and there would be this double entendre, this sexual happening, and so we then draw upon that history, so Ruckus, Porn Star, [unclear], Star Trek and all that kinda stuff and so really, some of the archive was then saying, actually, there is a history here and from that we need to then just change the [unclear] slightly and say we have been creating work and producing, and so now let us have another dialogue and because then I think that very few of our black queer work starts from aspirations, celebration, pleasure, joy. Actually, we’re saying actually there’s these other conversations that we need to have. So it’s kind of, that’s how it kind of unfolded.

INTERVIEWER: You can definitely see it in the work you did for Fierce as well. D’you wanna tell us a little bit about that?

AJAMU: Yeah, so fierce was a word that was mainly used by black, African American gay men during the 1980s and fierce is that little bit extra, y’know. And because y’know, if you think about [unclear] fighting fiercely and so fierce has this double entendre going on, right yeah it’s something else that’s fabulous and yeah it could be quite dangerous or whatever. And fierce was also around, okay a second generation of black British-born LGBT people. Basically those of us who were then born during the 1960s that early part would be considered the first black British-born generation in the context of the UK. And so those of us who identify as LGBT would then be seen as the out generation, and that means then the first AIDS generation, right yeah? Right. And then because once you hit 40 in the scene you are an elder [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: Thanks for that.

AJAMU: So, basically I – for me, it’s around kind of a few things actually: who are the young black queers I’m really excited by, who I think people really need to watch out for, right yeah. That was one kind of layering right yeah, and the other layering was around actually, if I was 18 years old, as isolated black gay man in Huddersfield and saw portraits of black queers, would my life have been different? In a sense, that’s the work, actually, what would happen if I saw these pictures right yeah, and now with Fierce, so I’m, and so most of the folks in there were kind of under 30 and now they’re more like 34, 35 onwards, yeah. So then my thinking is like there is now another generation of young black queers in school or just coming out of school, looking for their reflection right yeah. They won’t be looking towards me cos I’m basically I’m removed, cos age etc., but they will then be looking towards the fierce people, and now there’s a new set of folks coming through who I’ve been working with – Steven Isaac, Kareem, whatever. So n ow, so then basically those young queers at school will then look towards the Stevens and the Kareems and so really kind of my [unclear] work is the archive of work.

INTERVIEWER: This is really interesting to me in the context of this project, West Yorkshire Queer Stories, because I did want to get down to, y’know before we wrap up, thinking about what you want to give to this culture, back to this culture for young black queer kids in Huddersfield today? So, how do they actually – it’s interesting to me to hear that you’ve been thinking about it and that is part of this conversation that you have with Fierce, that’s something that I was interested in finding out. Have you taken that work up there, have you, has it been shown there?

AJAMU: No, I actually would love to – I’d love to see some of the work of [unclear] or somewhere like that. I [unclear] project Fierce 2 right yeah, and Arts Council, for the record, would not fund it. Right, yeah, right. And so Fierce 2 would be around the black, the black queers who are living up north – Huddersfield, Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool – because while I’m, lots of the materials in the Ruckus archive is London-centric yet, a lot of the queers come from these small towns that I come from.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, and here’s the conversation.

AJAMU: Yes, so basically so, so I’d love to do a project and I’m actually now that documents some of the younger queers coming through – and to really kind of – the work is about: we were here. That’s it. And that’s it. And the people they could take from that what they will, and I’m saying actually, there is, there’s times I walk through Huddersfield and I might read someone as being a dyke or a queer, I’m thinking, ‘how the hell are you surviving here?’ And as events, that’s why I’m, I’m – when we did the [unclear] project and I went to Manchester, Liverpool, just like kind of get more stories in there, cos basically I think that I yeah always have to look back to those towns that we come from and say , well actually, how’re queers in this moment surviving or not in these very small towns. So yeah, so Fierce and the archive is constantly about reaching backwards and forwards around that.

INTERVIEWER: And so are you from Huddersfield, or are you from London?

AJAMU: I grew up in Huddersfield but was made in London. And my heart is in Amsterdam [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: It sounds to me like so much of your experience was actually made in Huddersfield, this moment you’ve described to me of standing outside the club and looking across the road, and watching and watching and watching, and there’s that one night where you dash over – that same night you meet your lover…

AJAMU: Yes, yes.

INTERVIEWER: That feels very formative.

AJAMU: Yeah, I think – no, I know. I couldn’t have done… what I’ve done over the years if I wasn’t born and raised in Huddersfield, right yeah? And then basically I also said, for the record, I blame my family for supporting my queerness because then I could do whatever I want to do. And so really, and so really, that’s it. Basically I have the people in my corner are still in Huddersfield, my family. So hence –

INTERVIEWER: They’re so open-minded?

AJAMU: I, it’s because, I was from a very close-knit family [laughs] I… yeah and… Yeah so basically, I said to people that I, people always get surprised when they hear that lots of us are out in our family, generation after generation, because people have bought into the notion that black families are more homophobic and etc. And then actually, me being out in my family is not uncommon. The thing is that, the thing is until our queer politics, yeah, brings in our mums or dads and siblings and aunts and uncles, until that happens en masse right yeah, the story will still be quite narrow. So, hence actually that’s why I keep saying that my politics was formed in that place of isolation but then I was also able to dress how I want and then experiment and all that kind of stuff. And then of course those kinds of relationships are built decade after decade after decade.

INTERVIEWER: It’s been so enriching talking to you. It’s, I came from a very small country town too and legged it, ran away, and I don’t go back very often but I know that as you describe, that sensation of formulating ideas about who I was and how I could be and need more, really, really still informs me today. And I’ve heard, I’ve read what [unclear] writes around being desperate to get out of Brighton and get to London, and that he was never gonna be the respectable boy that his mum and dad wanted him to be in the [unclear] and he needed London to do that, so I think there’s an experience that we share across borders and regions with people that are about migration that bring us together creatively and culturally in creative space where we find each other.

AJAMU: Yes, you’re right. Yes, yes. Basically, some of us cannot survive in those small towns and that’s reality. And so basically, I’ve lost friends, through suicide or whatever, from those small towns, and so, so basically, I just kept running [laughs]

INTERVIEWER: And it’s great to hear how, it’s great, on the record, that Huddersfield has a place in this history and this –

AJAMU: Oh it’s central. It’s really central, and then the thing that people miss about my work, right, yeah – yes, some of the work is sexual right yeah, but the thing that people miss is my northern-ness. And cos we generally are quite plain-speaking whatever – that’s the work. That’s why it kind of – people don’t really try, it’s because people get locked into my racialised identity. They don’t talk about my identity in terms of the location, around being northern, and what does it mean to be northern. Normally, y’know, I’m quite open, quite plain-speaking, don’t take shit, don’t take rubbish. I, y’know, chocolate is chocolate, I’m not confectionary [laughs] And y’know, so that way of speaking, I think, comes from my work. It’s because it’s quite plain.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, nail that a little more for me. What visual indicators are there in the physical shots that you would read as this, this, this northern… transparency almost?

AJAMU: I don’t think you could read it in the work, I think you could read it in terms of some of the energy of some of the work, yeah? Basically, I am working around the body and sex quite openly and quite frankly, quite plain-speaking actually, so it’s that as informs the work. And also, the thing that people also miss is my Jamaican-ness, because there was again, Jamaica’s also quite plain-speaking [laughs] quite sexual, etc. So, in a sense, being Jamaican and northern – all of that is in the work. It’s the energy of the work, it’s the feel of the work. It’s how I could, let’s say, being at the event we did, talking about my dick is an archive, just openly is because I don’t kind of dress things up, and that’s part of my cultural background. So, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: I think that’s fantastic. I… I feel when I look at your work… I get that, that… energy, which is a loose word, but the way it sits there in front of you, unapologetically, but that also talks to my queerness.

AJAMU: Yes, yes, yes, well yes. As well, yes. You have to really kind of, it’s all in there, and so yes… Being raised in a town is central to my thinking, and I’m, so that’s the bit that people miss, that I’m a northerner. I’m not from London, I’m from Huddersfield.

INTERVIEWER: That’s a fantastic way for us to end it.

AJAMU: Thank you. I hope that was useful for you babes.

INTERVIEWER: Really, really, really spot on great, fantastic, thank you my friend.

[END]