Ahmed: Full Interview

Interview recorded by Ross Horsley on 4.3.2019

Duration 27:23

TRANSCRIPT

AhmedInterviewed by Ross Horsley

4 March 2019

RH: This is Ross Horsley recording for the West Yorkshire Queer Stories project, on the 4th March 2019, and I’m here with Ahmed. Ahmed, would you like to introduce yourself?

A: Hi Ross, my name’s Ahmed, I’m 35 years old. I’m a gay man, and I’m from Bangladesh and I’ve been here in West Yorkshire for – it’s a little over 2 months now.

RH: And what was it that brought you to Wakefield?

A: My partner lives here, so the first destination after arriving at Heathrow was Wakefield.

RH: And why did you come here?

A: I came here because I am afraid of my life, I am being prosecuted and my life is under threat.

RH: Can I ask you what happened to put your life at threat?

A: Yeah, sure. This – my story goes back in 2016, actually before that, like apart from my main job – I used to be a bank manager back home, I’m also an LGBT activist. So, a group of my fr – with a group of my friends I was involved in gay rights activism. In 2016, in March, we held a LGBT rally in Bangladesh, which was the first of its kind, and it was taken as a big shock, it came as a big shock – it was all over the media, it was everywhere. So after that we started receiving threats from Islamic parties, and that Islamic parties is sort of in bed with the government that’s in power, so they’re like very powerful. So in the month of March – the rally was in 14th March – the phone calls were frequent, and Facebook, so I deleted my Facebook, my social media presence was zero. It was so high that I went to the Philippines for a couple of days so that things settled back home. But the day I reached Manila I saw in the news that – breaking news coming in, BBC, that LGBT rights activists hacked to death in Dhaka, so I knew that someone I knew has faced the consequences. So it was Xulhaz Mannan and Mahbub Tonoy. Xulhaz was the editor of the first LGBT magazine in Dhaka in Bangladesh. We were able to publish only one copy. I have the copy with me now, so before leaving Dhaka on the 24th I met Xulhaz, he gave me a copy and I told him that he should go somewhere, hide somewhere. His answer was, ‘What – the best they can do is kill me, I’m gonna stay, so you can y’know go and have a holiday anyway’ – so that was his last word, words.

So, yeah, after receiving that news obviously I was devastated, I was worried about my life as well, so I stayed there for a month. So, if you stay away from your work for a month you know the consequences, so I was made redundant at the bank I was working for. But I came back after a month and then managed somehow, but then things we had achieved together somehow went like 50 years, it took a reverse, everything it was destroyed. We couldn’t find justice for him. We had to hide ourselves, I had to change the way I even look – I started keeping beards, I cut my hair short so that I’m not easily recognised anywhere. So yeah, because in the media – we realised that the people who broke into Xulhaz’s house used gay platforms such as Grindr, Facebook, so naively and bravely we must have opened our houses for the enemies and that’s how – because Xulhaz was working for the US embassy, he lived in a protected environment, but they were able to break in even that house. So yeah, life was very difficult.

Then in 2017, the following year, in the month of August, Attitude magazine, which is, which claims to be the biggest LGBT magazine in the UK published an article where it says that – published an article on LGBT situation in Bangladesh. So there was a picture published there where me, Xulhaz, and a few other activists were there, so this magazine sort of went in with the wrong hands again, so it was 2016 repeating all over again. The next month – at that time my boyfriend was in Leeds, so I told him that this has happened, so he was working for Yorkshire MESMAC at that time so he immediately informed his colleagues and there was a kind gentleman, I think she or he is the operation manager, CEO of MESMAC, he got in touch with the editor of the Attitude magazine and the online content was taken off the internet. But the damage was already done.

In September, four men tried to break into my house. It was the same style of the way they broke into Xulhaz’s house the previous year – they had machetes with them, but thankfully y’know, my security guards – because I live in a, I used to live in a house where there were securities. So they were caught, my brothers were able to stop them, but my father who’s 70 years old, he got hurt and he had a big – he was hurt in his head. So they couldn’t get in – three of them escaped, but one was caught, so and there was a big commotion, the neighbours came in and this guy started shouting and they were on drugs because this young guy – skinny young guy – with immense strength, so he was able to fend off like four of us, like he was – so when his, the power of his drugs went off, he started talking and he was shouting that, ‘Do you know why I’m here, I’m here for that guy and he’s involved in such such things’, so my cover, like all these years I have managed to stay under like y’know, nobody knew about my sexual orientation, so this was like, this all blew up in front of my own family, and a few of the neighbours, which was very embarrassing – I mean, I can’t, I don’t have the words to explain because it was my own father who’s bleeding, my brothers y’know, so immediately I went into hide, I left home.

So it was difficult, and then in the back of my mind I knew that they have discovered where I lived, so the Facebook threats I started receiving after the magazine was published was real, so even if I have changed my phone number two, three times in between, they have found my phone numbers. And they also must have known the place I worked now, so it was really difficult so I went to stay with a friend, then yeah – I had to escape, because I wanted to live and I couldn’t go anywhere else, I couldn’t go to a different city because these people are so powerful, because the problem is the guy who was caught, he was given to the police and Bangladesh police – it’s another story. They, instead of pressing charges against him, they came back to my father asking for bribes because there is a law that – Section 377 – colonial, y’know ‘gift’ to Bangladesh, it says, which says that gay men are to be imprisoned for life.

So, my dad was taken aback, he sort of dropped charges because he realised that this will go against his own son. So this was very embarrassing, very yeah, humiliating as well. So yeah, that time I started having depression all over again. I had suicidal thoughts, so yeah, then I decided to come here. I applied for a visa, but I was refused, so, a normal person would have waited six months and reapplied, because that’s what travel agents tell us, that y’know if you are refused a tourist visa you should wait at least six months, that’s how it works. But I was so desperate for my life that the day I got my passport back, the next day I applied again, but this time luck played, I was given a visa – I don’t know how, this was sheer luck. Yeah the moment I got my passport I just got on a plane with the same pair of jeans I was wearing and my laptop bag. It was a twelve hours journey and the whole way I was crying I had no money on me, only hope, only confidence I had that my boyfriend was here and I have a place, y’know, I have a shelter.

And then suddenly when I opened that laptop bag, the publication was there and this is – it’s got lots of emotional value. It’s a keepsake because I got from the hands of Xulhaz and that’s the last time I saw him. Yeah, so we start, we wanted to keep his memory alive, after his death, because we couldn’t go for print media anymore, because it’s dangerous, we can’t just go to any printing press because people raises eyebrow – because in Bangladesh, this word gay, lesbian, it’s dealt with – it’s too much stigma, I mean, people will laugh at you, people will bully you, raises eyebrows, so you can’t just go to any place. So we decided to go online so Project Dhee has gone online, we have a blog now and I still continue to contribute there. I write blogs there. We have a small audience, but there are a lot of people like us who, young men who go through depression, they have suicidal thoughts so if anyway we can provide support for them, because that’s what we used to do, we used to arrangement parties, seminars, so that people can come and be who they are, because depression is a big problem there. We are forced to get married to, into y’know heterosexual marriages, which is often devastating, so yeah we’re online now, Project Dhee – so this is the first copy, which I’m, which I’d very much like you to have for West Yorkshire Queer project can have it, so that our story is kept.

RH: Thank you. Would you like to describe a little bit what this is, what it looks like and who it’s aimed at?

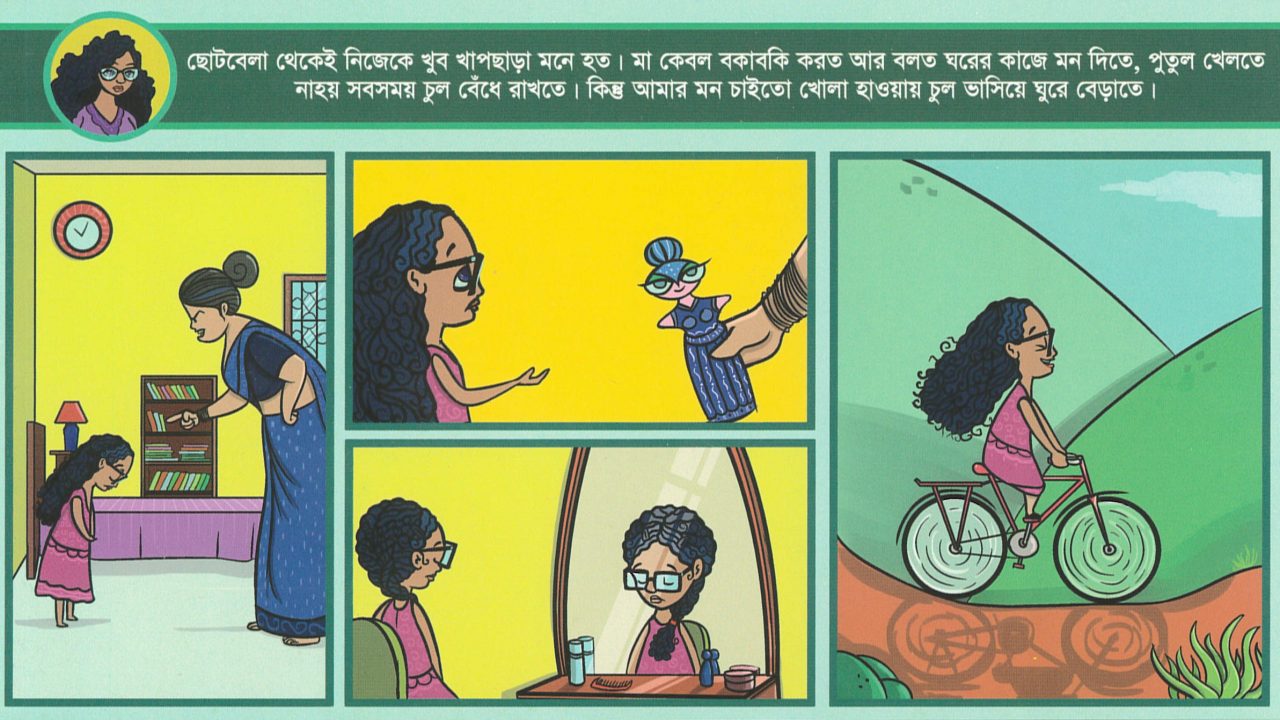

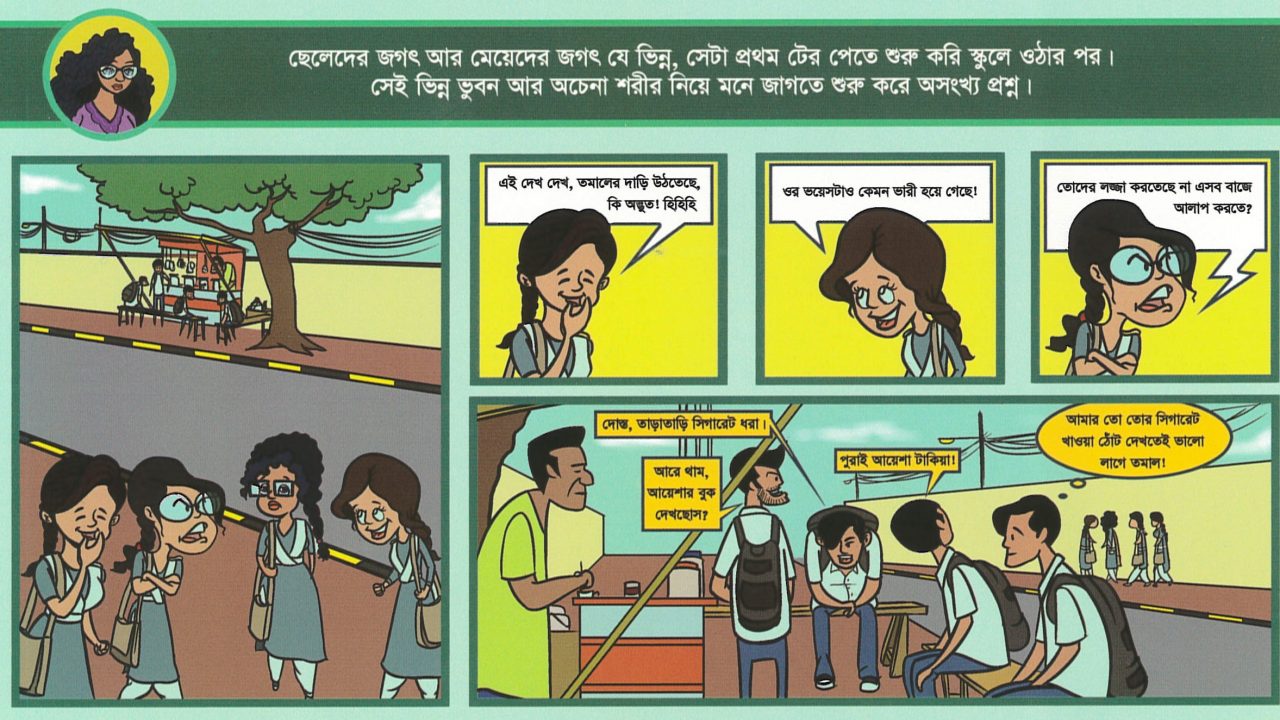

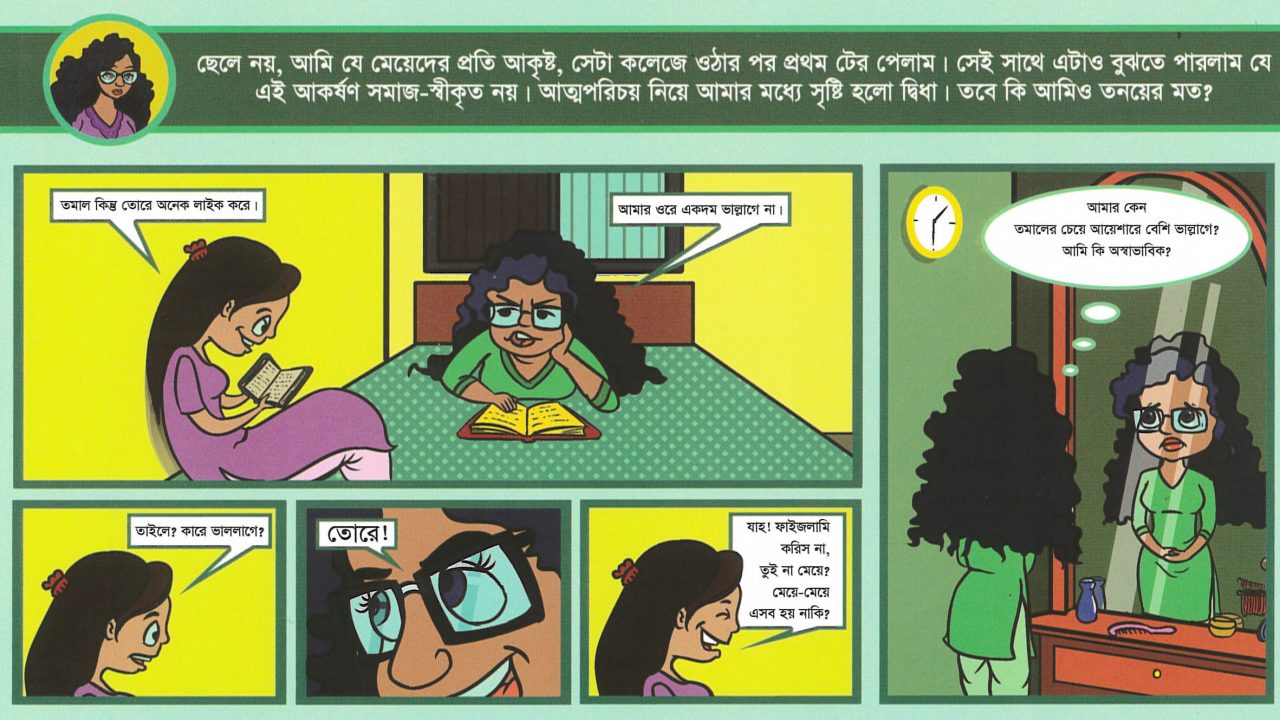

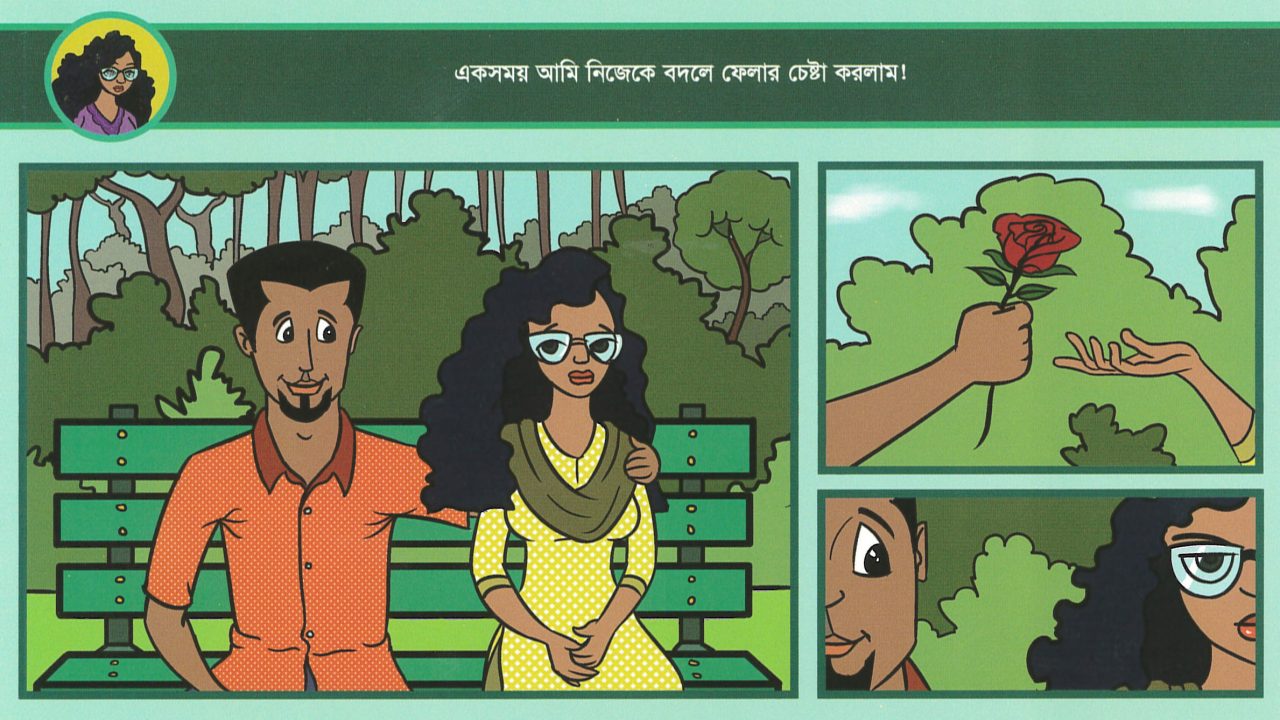

A: So, it’s called Project Dhee. Dhee is the name of a girl, she’s 18, and we sort of have ten flash cards – these are called flash cards, right? So, in these flash cards we sort of go through her adolescence, that part of her life where she was growing up and her mother wanted her to be like other girls, other young girls – play with dolls, put on make-up, y’know – but she wasn’t like that, she realised that time she wanted other things, she wanted to y’know have a bad hair day, ride bicycles like boys, y’know travel a lot. And at the back of it, we – so that’s described in pictures, this life and transformation, and in the back side we are providing information, such as what does gender means, what does social gender means, what sex and gender behaviour is. It’s written in Bengali, but I can have it translated for you. It’s just definition of things. So, one by one, we go through these life. She goes to school, when the boys are checking her out she doesn’t find any interest in boys because she’s obviously a lesbian girl. And the boys also, they’re passing bad comments on her and she’s like, she tells her girlfriends that she has no interest in boys and they are having a laugh.

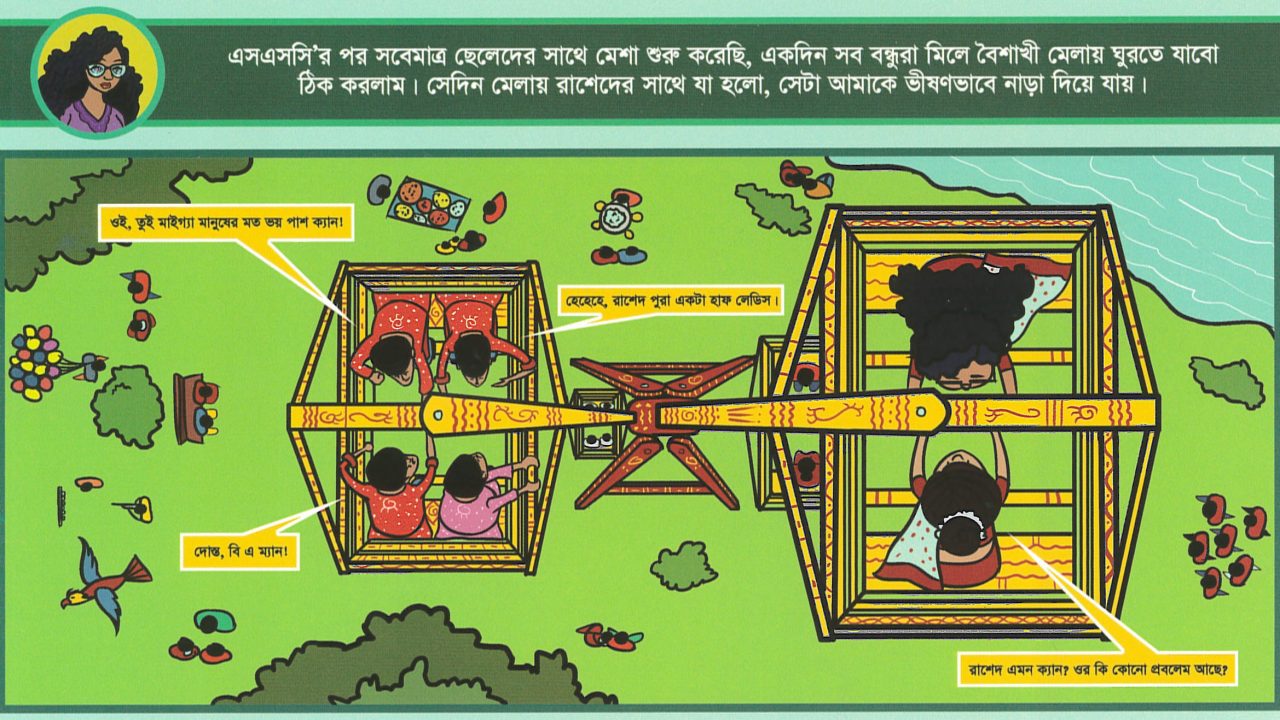

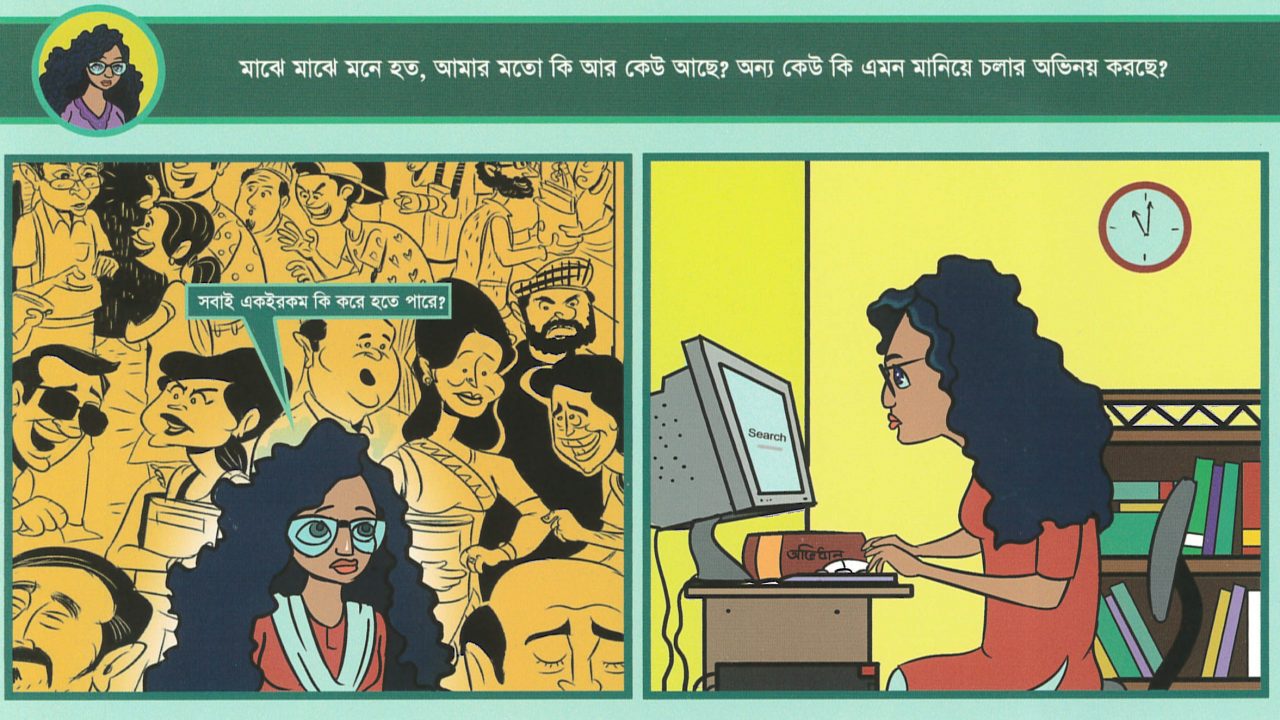

Then she goes to a fair. It’s a Bengali New Year fair, where something happened to her, which had a big impact on her. All of her friends – amongst her friends there was this guy who was a bit feminish, so we’re trying to say here that he had like bit girly attitudes. So in the, all her classmates were bullying him or her, so she’d started thinking that why is this like this, why are they bullying him, he’s just a normal person. So that person as well, he was going through a transformation. In Bangladesh, transgendered people are called hijras, they have the most horrible life a human can have. They are neglected, bullied – even in death a priest wouldn’t bury them, so you can imagine, they’re denied all the rights of human being. So then she finally tells her, one of her friends that she likes her, and obviously that girl was mortified and rejected, and so she had a bad time after that confessing to her friend. She wanted to become normal like the society wanted her to be, she goes to get a boy, normal boy, and then it was a fight, she could not do it. So the pressure was tremendous from the society. Everybody’s telling her that, look around you – everybody’s getting married, having babies, grandchildren, when are you gonna do this? So she – this – she goes on a soul searching mission. She goes on internet and starts finding, and she finds like-minded people.

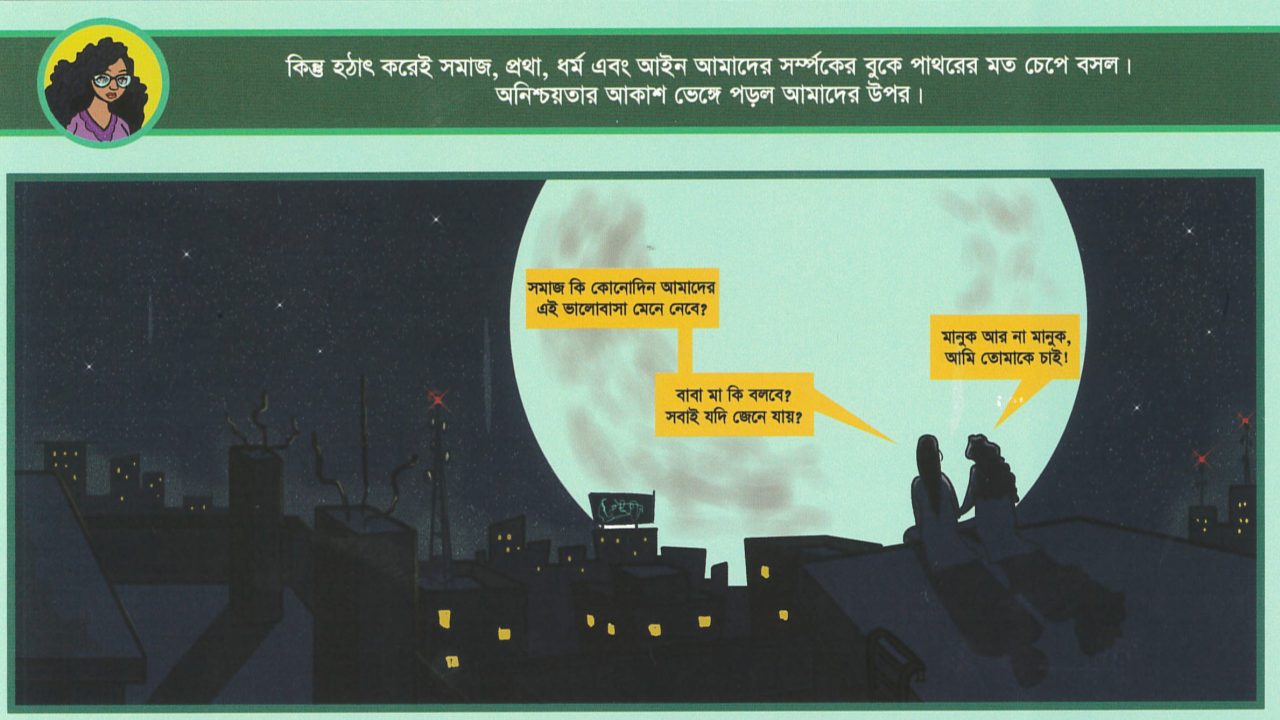

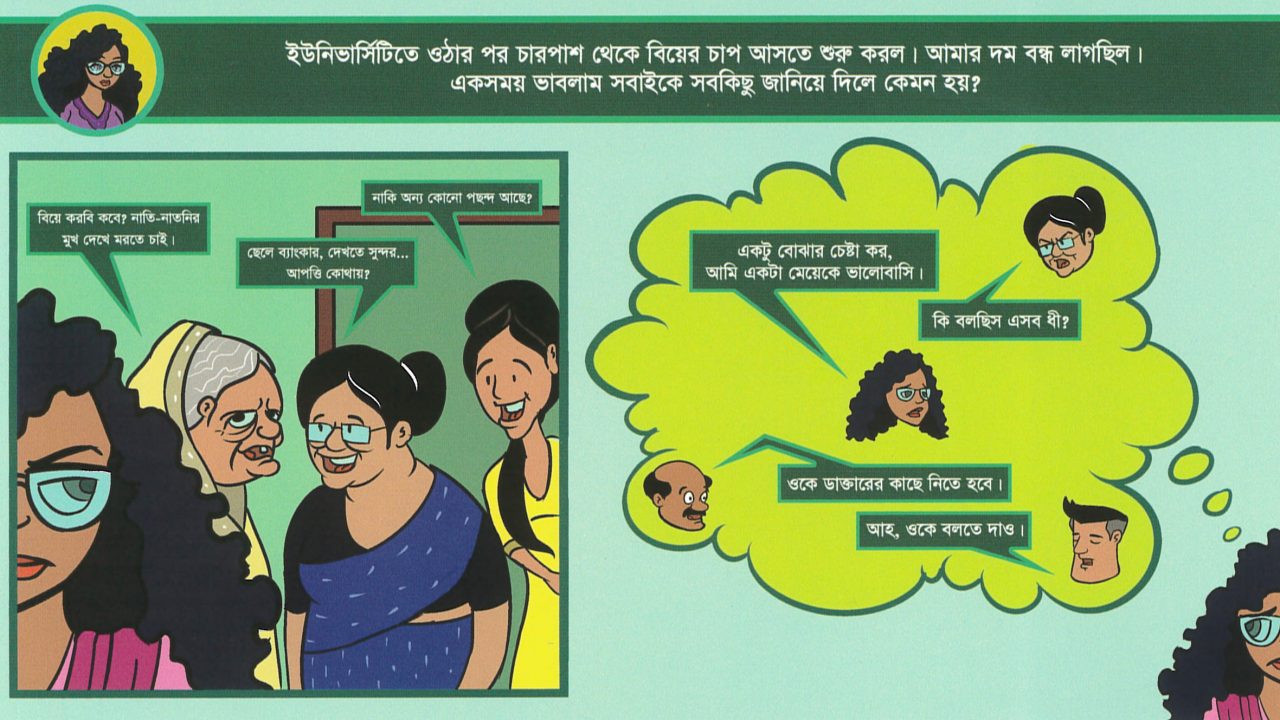

Finally she finds a girl, and she falls in love with somebody, and this is a very… this is a perfect time, the most beautiful time of her life. She finds somebody, and that person loved her back, so these two girls – this is a moonlit night, they promise each other that no matter what happens they will stand by each other. So but as she grows old, like she comes to a marriageable age, she’s 25 now. So in this picture, her mother, her grandmother, everybody’s like pressuring her to get married. Grandma, who she loves a lot, wants to see granddaughter, grandchildren, y’know, social pressure. And she decides, should I tell them, should I tell my family that she loves girl, that I love a girl, but y’know, she’s imagining it – it’s not possible because the consequences will be devastating.

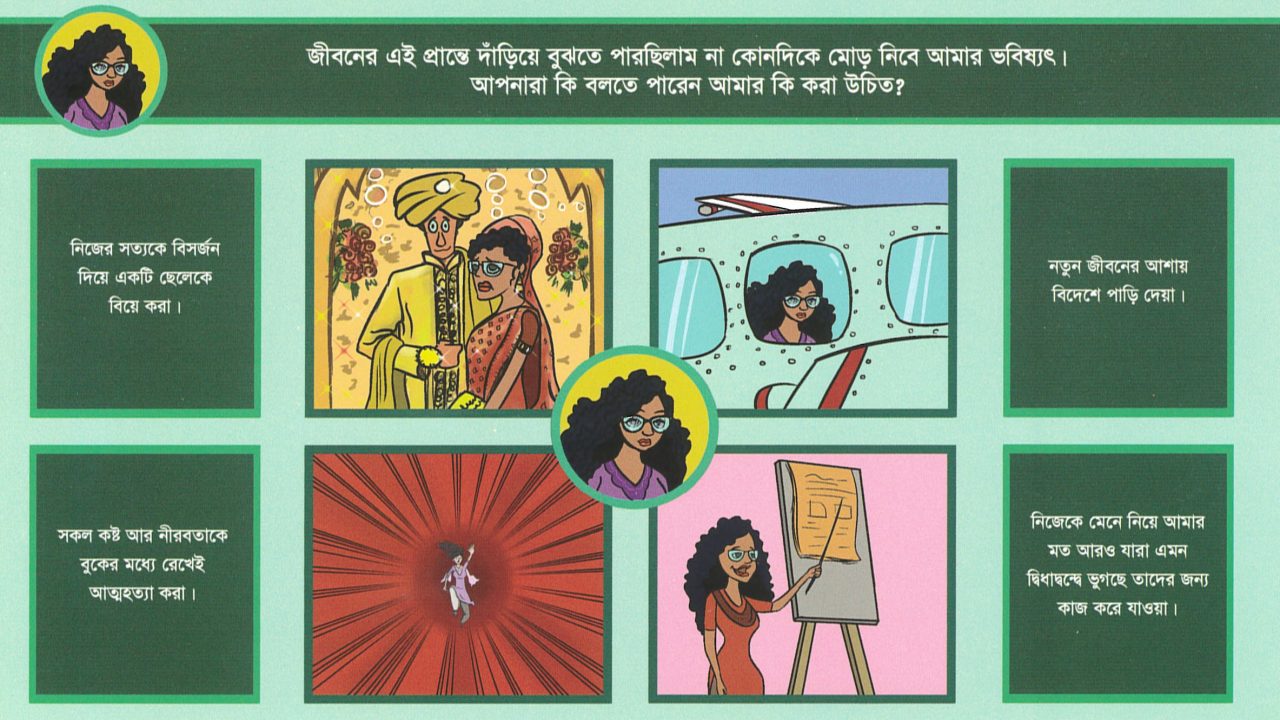

At the back, again we are providing information, like what does coming out means, why is it important, what is homophobia, things like this. So in the end, at this point of her life she realises she’s left with four choices: she can sacrifice what is truth and get married to a guy and be unhappy for rest of her life; she can commit – she has suicidal thoughts, she wants to end it all; she can search for a new life and leave the country, and go to a place where she can be herself; or, the last choice she had, she can accept herself and she can work for people like herself who are going through the same difficult times, so she can either become an activist or something. So that’s how it ends, yeah, that’s the story.

RH: Did you have access to materials like this yourself back in Bangladesh?

A: We had access to publications that are y’know for normal people – by normal I mean general people. So we did take ideas and this design was done by one of our friends, he goes to university, we have a University of Charukola, which is the art and craft department so these designs were done by him, so and the information we, most of them we collected – like the definitions, we collected from online, we have also given references overleaf, yeah, so yeah we had… but then we sort of designed this and the words are chosen very, very carefully because this – we didn’t want to y’know stir a commotion because words like gay, lesbian, same sex, these are very trigger words in Bangladesh so we have to find different words, make it look as normal as possible, which was very hard work as well.

RH: What did you plan to do with Project Dhee?

A: Project Dhee’s next step – first step was letting people know of the presence of Project Dhee. So this was sort of the advert so people, this was aiming – the aim was this publication was to let people know that people like this are within our community, people exist within our community, that they are normal people. There’s y’know nothing bad about being a gay person or a lesbian person, and they have rights, so next step would have been talking about the rights that we have and also the dangers, so we would have addressed HIV and STDs, so that was y’know – the plan was like this but, y’know, we couldn’t materialise.

RH: Can I ask you, are you still in touch with your family?

A: My family… I left in December – no actually I left home in September 2018. I went to stay with somebody else and I wanted to go and pack my bags, because obviously all my belongings were at home but I couldn’t, I wasn’t allowed to get in because my dad – mom was extremely furious, she had always dreamt of having a daughter-in-law, having grandchildren, she had high hopes. My brothers, my brothers’ wives, I mean, they had high hopes. My dad – I imagine, I mean, this must have been so hard for him, and I feel so guilty because now he knows from somebody else what I was up to. I have failed him – I feel like I have failed him. I had a phone call, a phone chat with him before I left. He said to me that, y’know, your actions have put my family and your bothers in trouble as well, so if you wanna, y’know… I have, his last words were, ‘I have taught you enough, you know how to survive this world so, y’know if you stay away from now it will be better for you, better for us’. Cos I can imagine he must have gone through hell because of me, which is very depressing actually. I never had the chance to – because coming out is impossible, it’s my society, especially with Muslims and the society it’s unaccepting and unkind so yeah I don’t even think about it so… yeah but as I grew up, I always knew that being a gay man is a lonely path. I have to, at some point, abandon my family, my friends, my – whatever I have known so far. I knew that but when reality came, to be honest, Ross, I mean it devastated me, as if I wasn’t prepared, but I all my life I knew that one day everybody would forsake me, because of who I am, because of who I love, but when the reality came this is absolutely different.

RH: How is life here different? Do you think it’s different for LGBT people?

A: Here, LGBT people together has achieved a lot, but there’s a long way to go also. Like, LGBT History Month I have attended your charity’s functions and I’ve been to [a] few other places where I’ve seen, had first-hand knowledge of y’know how life was here, and people have suffered a lot for being who they are. I mean, there was discrimination, there was y’know everything. It wasn’t easy for people y’know here as well, so yeah – but this is a safe place, I mean, at least now things have changed and it’s part of human rights, they are recognising it, which is good and I just – I can only hope that one day we can make difference for people who are stuck in places like Bangladesh or other Muslim dominated countries that we can change the scenario for them. Because if a powerful country, if people of a powerful county can speak up and it changes a lot in people whose voices are not heard.

RH: Thank you very much Ahmed.

A: Thank you for having me.

[END]