Having ‘queer’ yelled at me across the street when I was eighteen was one of the worst experiences of my life. I’d just written an open letter to our MP and local newspaper to call for equal marriage and upset a lot of people. I was so ashamed and scared. Now, I couldn’t imagine calling myself anything other but Queer and am proud to have been even a small part of this incredible project, transcribing and selecting clips from interviews.

I grew up in a rural town in North Yorkshire where everyone knew everyone. Gender and sexuality were taboo subjects, never discussed or questioned. Growing up with no one to talk to about all the conflicting feelings I was experiencing was hard, coming out was even harder, but moving away from it was the worst. Not because I missed anyone, but because I didn’t miss it at all. Leeds has been my home for the past eight years, the last two of which I have spent studying towards my MA in Curation at Leeds Arts University, whilst living with my equally Queer partner and our rescue dog.

A bit like my rural town, the museums, galleries and heritage sites I have spent a lot of my life visiting have always viewed subjects like gender and sexuality as taboo. Most of the collections and archives these institutions are built upon have traditionally been collected, conserved and curated by the wealthy elite – predominately white men, with little regard to the very real human stories attached to the objects they stored and displayed.

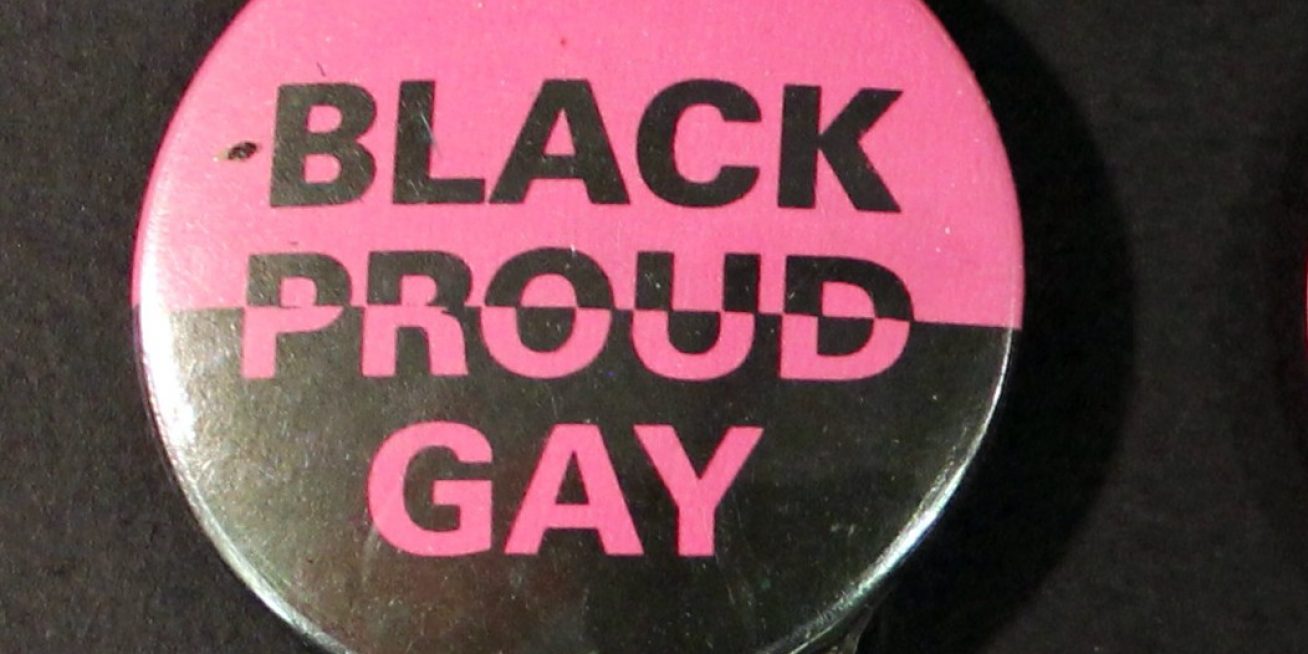

A huge international change is currently underway across curatorial and museological practices, with more focus being put on telling stories, connecting us with our past and culture, and representing the broad diversity that makes life so unique. This revisionist approach to accessing our collections and archives helps us to unearth hidden identities from invisible communities, patching up the gaps in our history and changing the social narrative being told in our public spaces.

No longer taboo, many institutions are embracing open dialogue about the human experiences under their care, allowing the public to be challenged and educated, and spreading awareness and tolerance for minority groups and difference. But it is not just to the past and correcting our forebears’ mistakes that curators must tackle.

We must also think about how we can collect stories and objects now, so that future generations will have more information than ever before, helping them to connect with their community and sharing everything we have all overcome. Within the Queer community especially – at a time when we have never been so seemingly free to express individuality, and yet so oppressed by dangerous ideologies – we must preserve our past, protect our stories, and collect evidence so that we never again have to hide in fear of who we are. WYQS is doing just that, working towards a better and brighter future, embracing our differences and sharing in our collective story, making all those lost, vulnerable and young LGBT+ individuals out there, as I was, feel heard, understood and normal.